Sometimes when walking in the woods in Eastern Massachusetts, you come up to a rock with a split in it and notice that someone jammed a rock or two down into the split. At first I noticed this without giving it much thought - probably having jammed a rock down in a split myself, one time or another. If you had asked me about it, I would have said it is not surprising to find these rocks in the woods, since there has been plenty of time for people to walk by and casually jam a rock down into a split.

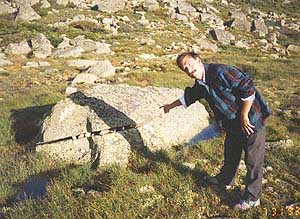

But, if you look, you will see a number of examples where it would take significant effort to lift up one part of the rock while putting in a wedge. Try to imagine how someone could build the one shown next. You can see it would be anything but casual. With an upper rock weighing a thousand ponds or so, this is not the work of a passing boyscout. Someone exerted themselves here.

I am not sure when I started paying closer attention to this phenomenon; it could have been while walking in the woods with friends and looking for examples of things that had been altered and showed signs of being the "works of man". We go out hoping to catch a glimpse of what the Indians might have done or might have left behind. I am sure we discussed whether some of the split-wedged rocks might have been done by Indians. There was also an article (online at Anthropology In the News; more specifically this is from Sally's Rockshelter and the Archeology of the Vision Questby David Whitley, Cambridge Archeology Journal (1999)) that talked about a practise among some shamans of the Mojave desert where they placed fragments of quartz into a crack in a rock, believing the crack was a doorway to the underworld and that they were making an offering to the spirits there. We discussed that and other theories about why an Indian would wedge a split rock and whether an Indian ever did that sort of thing around here.

No doubt plenty of split-wedged rocks could have been created by casual passers by. Maybe wedging rocks was a popular fad at some point. Maybe it was done for a practical reason. But even when split-wedged rocks could have been made without much effort, I look at some and wonder: what kind of impulse led a person to do that? Sometimes they are quite aesthetic:

Other times they seem like distinct structures with a specific purpose.

Split-wedged rocks do not appear everywhere in the woods. There are places where the rocks have lots of splits and no wedges (for example in Falmouth on the Cape) and other places were there are lots of splits and lots of wedges. Sometimes they seem to be done compulsively in a certain area, following a principle like "no split goes un-wedged". For example, if you are driving north on Rt 3, as you pass under Rangeway Rd in Billerica there are a half-dozen or so split-wedged rocks in the woods on either side. Somehow, there, most of the split rocks got wedged - as if it was important to someone.

I observe that split-wedged rocks are not very common in dry woods. Rather they are usually adjacent to where water comes out of the ground, at a spring. They are often found near the base of a hill but are rarely near the top of a hill. They are usually found near rock piles. To continue with the example of the crossroads of Rangeway Rd and Rt. 3 in Billerica, here there was a stream, or a water source, that drained eastward. The woods, in all four quadrants cut by the roads, show multiple signs of the "works of man", including rock piles, little walled embrasures, and large rock fragments - broken off of one rock and placed on top of another. There are many small modifications to the rocks here which, individually, would not seem remarkable; but taken together suggest an unusual activity at this location.

One thing is certain: the wedging of rocks is widespread in the woods north of the Concord River. I have looked and found very few of them south of the Concord river. This could be a matter of not looking hard enough, though I have tried to explore conservation lands, state, and some private property, in all the towns surrounding Concord Mass. Split-wedged rocks are common in Acton, Carlisle, and Billerica, and in northern Concord, but they are rare in southern Concord, Bedford, Lincoln, Lexington, Sudbury, Weston, etc. I have looked but only found one on the Cape, and did not see any on a visit to western Mass. Looking further afield: there are some split-wedged rocks at Madison Springs in the White Mountains in New Hampshire, between Mount Adams and Mount Madison. When it comes to a split-wedged rock above tree-line in the mountains, we have something which is neither casual nor practical. So what is it?

I have asked a few Indians about split-wedged rocks and some say they have seen them (as far away as in Michigan) but don't know what they mean. I asked Jim Mavor one of the authors of Manitou, a source book on Indian prehistoric ceremonial stone work, and he has not noticed split-wedged rocks.

It is worth entertaining the possibility that these are not casual items but, at least sometimes, were built with effort and for a reason at specific locations. I cannot imagine a colonial farmer, or anyone else leading a purely practical life, taking the time to go wandering systematically though the woods wedging rocks. Nor would casual creation of split-wedged rocks have resulted in them being concentrated in certain locations and not in others - why are there more of them north of the river than south of the river? Why, in some places, does there seem to be something compulsive going on, something almost ceremonial? And this leads to speculating about the Indians. The Indians did live around here, they did work with stone, and they did pursue ceremonial activities involving the natural landscape. Also they might have been limited by natural territorial boundaries such as rivers. The Indians are good candidates for who, besides casual walkers or practical landworkers, could have created these "works of man".

If split-wedged rocks were made by Indians, what could have been the reason for it? The article I mentioned provides a clue but one speculates in different directions. Several people have come up with this explanation: that the wedge represents an insemination of mother earth, as represented by the split. The association with springs, water, and fertility makes this plausible; and some examples certainly provoke that thought.

I told a collegue at work about split-wedged rocks and he came back the next day, excited because he had figured it out: "If a crack represents a doorway to the underworld, and a spirit comes out of the crack, then you need to prop the crack open, so it doesn't shut and trap the spirit outside". This is my favorite theory and the reason we sometimes call split-wedged rocks "Spirit Doors". Possibly, if the notion of a doorway is appropriate, some splits could be filled with multiple rocks to block the doorway instead of keeping it open.

In any case, split-wedged rocks are a real phenomenon, possibly with multiple "causes". They are not all ancient, and a lot of time the split is not natural and is, itself, the "works of man". Here is an example where the split was made using a steel drill, and then a thin wedge of rock was inserted. Perhaps it was not the same person who split the rock and who wedged the split. The drill work on the rock looks like standard colonial rock splitting. A large fragment has already been split off and a nice piece of granite has been removed. But then someone took the time to insert a thin wedge. In this case maybe there was a practical function for the wedge and they just left off work before it was completed.

But that doesn't explain most of the examples illustrated here. When a rock has been deliberately split and a portion is missing, it is fair to assume that getting a nice piece of rock was the motivation for doing the work. But what are we to think when a rock has been deliberately split but no fragments removed? That is the case for several examples illustrated here (eg the third and fourth picture above and the one below). Is it possible some rocks were split deliberately, simply in order to insert a wedge and leave it at that? Is it possible that colonial farmers split rocks because they were tired of the Indians performing worship there. [as described several years ago in a Boston globe article about Carlisle, but I cannot find the reference] and in some of those cases the Indians came back afterwards to wedge the rock so the two halves would be again joined - thereby partially restoring a vandalized rock?

Like detectives who try to reconstruct the details of an event, it is fun to look at a split-wedged rock and try to imagine a scenario. Is the split natural? Was any rock removed? Could the wedge have been used as part of a process for splitting the rock? Is the wedge a different kind of rock? How much strength would have been required? Could it have occurred naturally?

Next time you go walking in the woods, keep an eye out for split rocks. When I see a split rock, I always go up to it and look inside - will it have a wedge? Ah! Peekaboo! There it is.