In Hopkinton, Rhode Island, in the southwestern part of the state, lies Miner Farm, a beautiful rural working farm located in rocky terrain. Crisscrossed with colonial walls, and bisected by a now-abandoned colonial road, it is also home to a number of intriguing stone features that I conclude are much older than the obvious reminders of colonial farming practices. A history of this farm is found in a web article by Jim Porter titled "Early History of the Miner Farm: Preliminary Report" (http://mentonmyjournal.com/minerearlyhistoryweb.pdf), which includes images of some unusual stone constructions not illustrated in this article.

In March 2007, Bob Miner, the present owner, showed my wife and me some unusual, possibly manmade stone features. Toward the end of our stay, he asked if I'd like to see a rock outcrop just south of the ancient colonial road where he said there was some odd stonework. I could not turn down an invitation like this, and soon we were tramping through the open cedar and oak woods to the outcrop. This outcrop and its associated stonework were so intriguing that I was determined to visit it again and spend more time studying it in greater detail. In early November 2008 I made my return visit, and what follows is an account of what I found.

Here in the Northeast, those of us who study cairns and other unusual stonework that we believe are American Indian continually have to confront the prevailing attitude among mainstream archaeologists that we are wrong in our conclusions, and all of what we see is Colonial, constructed after the invasion of Europeans in the early seventeenth century. According to these archaeologists, the Indians did not learn how to build walls or anything major out of stone until the English came and taught them how to do so. These views were outlined in the 2007 issue of Terra Firma 5, the publication of the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation's Historic Landscape Preservation Initiative. In a box at the end of the newsletter, titled "The Last Word: Debunking the Myth of Stone Walls, Piles and Chambers", the unnamed authors wrote that there was no archaeological evidence to support the view that any stone walls, cairns or chambers found in the region were Native American. Farmers would "pile surplus rocks within pastures for later use of sale." In other words, anything we find in the woods has to do with colonial agricultural practices, such as field clearing, and nothing else.

To counter this, and in the absence of diagnostic artifacts that might help establish the age of cairns and other structures, I and a few other researchers have resorted to a number of different approaches to prove our argument. For myself, this includes in many instances a deed search, scouring the historical literature for information about the site or features being investigated, walking through the site and observing the landscape and local geology, seeing how various features relate to the landscape and to each other, photography, plus wide reading of ethnographic, anthropological, and archaeological literature that sheds light on Indian beliefs and practices as they might relate to the cultural landscape. In one way or another, all of these are brought to bear on the topic at hand, and hopefully it is a combination of these that will prove the case I am trying to make. This approach was recently outlined in an article of mine titled Accenting the Landscape: Interpreting the Oley Hills Site (Muller 2008) and one by Herman Bender ("Seeking Place: Living On and Learning from the Cultural Landscape") in the same publication (Bender 2008).

Let us now examine the outcrop.

We approach the outcrop from the northeast. From a slight distance the heavily fissured outcrop rises, dome-like, from a low knoll. It is 1.5m high above the surrounding terrain on the north side, increasing to 2.5m on the sloping downhill south side. It is also roughly 8m in diameter (Fig. 1). The woods are fairly open, with pines, cedars and oaks predominating. Other large glacially worn boulders lay scattered around it. When I first laid eyes on this outcrop more than a year ago, I thought of what Joan and Romas Vastokas wrote about the Peterborough petroglyph site in Ontario: "Boulders, rocky hills, and outcropping with unusual dimensions or character, such as clefts, holes, or crevices, were especially charged with Manitou and often conceived as the dwelling-places of mythological creatures" (Vastokas & Vastokas 1973, 48).This seemed a perfect example of what I was seeing, and further investigation would bear this out.

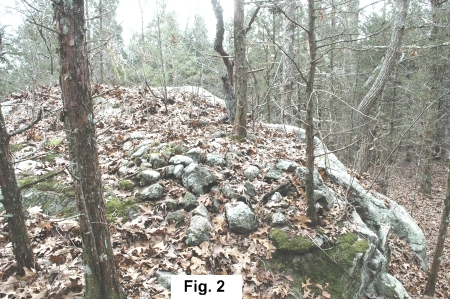

As one approaches the outcrop, one immediately notices that the sloped north-facing side is covered with small fist-sized rocks, heavily patinated with lichen (Fig. 2) and partially covered with moss and soil. There must be hundreds of rounded, fist-size and slightly larger stones randomly distributed over the surface. While some might conclude that farmers could have tossed loose rocks on the surface as field clearing, the heavy lichen patination of the rocks with the moss suggested great age. It was at this point that I entertained the idea that the stones were donations. There are many accounts in the colonial literature of educated individuals like Ezra Stiles observing Indians tossing stones on stone piles as they passed by, the piles often being memorials to dead warriors. Timothy Dwight, on a trip he took through New England in 1798, described a large stone burial mound on Monument Mountain north of Great Barrington, where every Indian who passed by threw a stone on the mound (Dwight 1821-22, II, 380-381).The stones on the outcrop in Hopkinton could be viewed in the same way: as a donation or gift to the sacredness of the spot and the spirits that resided within.

Walking around the outcrop in a counterclockwise direction, the first thing one encounters is a large vertical fissure filled with stones (Fig. 3).This fissure is probably an extension of the larger one visible on the other side of the outcrop in Fig. 1.The stone cobbles do not appear to have accidentally fallen into the crack by those who deposited stones on top, but instead were deliberately wedged in place.

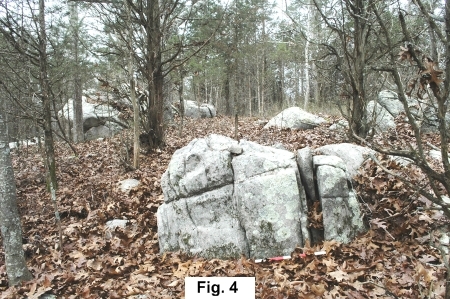

This type of feature, which I and other researchers refer to as a split-filled boulder, is simply a larger and more elaborate version of the single split-wedged boulder, an example of which is found only 9m northeast of the outcrop (Fig. 4).Both examples are common in southern New England and especially Rhode Island, where Larry Harrop, an investigator of rock feature sites, had recorded 81 examples of the former feature, and 39 of the latter (Larry Harrop's Rock Piles). Next to cairns and stone piles, these are the most common stone feature to be found in the region. While one might think that this is just a local phenomenon, it is actually found across North America. Examples are known from Georgia and Minnesota, but it is in California where it has received the greatest scholarly attention.

David Whitley's 1999 article on Sally's Rockshelter helped place split-wedged and split-filled boulders in proper perspective. In investigating this large shelter complex in the Mohave Desert of central California, Whitley found fissures jammed with six unworked quartz cobbles (Whitley 1999, 226 and Fig. 5). Considerable ethnographic research by Whitley and others has uncovered evidence that rocks were considered numinous by American Indians, with the spiritual world thought to reside in these rocks. Furthermore, "cracks in the rock were conceived to be portals into the sacred realm" (Whitley 1999, 234).The quartz stones found in the cracks at Sally's Rockshelter were thought to be offerings to the spirits residing in the stone, which could freely pass in and out through the cracks. Based on the pecked petroglyphs that were found underneath the overhang of the rockshelter, which suggested the visions of someone in a trance, Whitley concluded that the quartz cobbles had been placed there by a shaman on a vision quest. Quartz was not found in the immediate area of the shelter, and thus must have been deliberately brought to the site from elsewhere.

Throughout the New England area, we find boulders, outcrops and ledges with large splits filled with one or more stone cobbles. There is a spectacular example in Fahnestock State Park in New York, where a large vertical outcrop with phenomenal attributes has a long, 2m long vertical fissure filled with stones (Fig. 5; see also Muller 2007). A large, wider example is also found in South Newfane, Vermont, which also has some interesting stone accents to either side of it (Fig. 6; see also Muller 2007, fig. 14). All of these examples, I conclude, are versions of the same expression as single stones wedged in cracks or fissures.

Similar views about how Indians viewed rocks and fissures were expressed by the Vastokases in their book about the Peterborough petroglyphs (Vastokas & Vastokas, 46,49).This again demonstrates that the Indians viewed the entire landscape as animated and charged with meaning. We must recognize, however, that this is a view and response not restricted solely to North America, but is instead world wide, and extends millennia back in time.

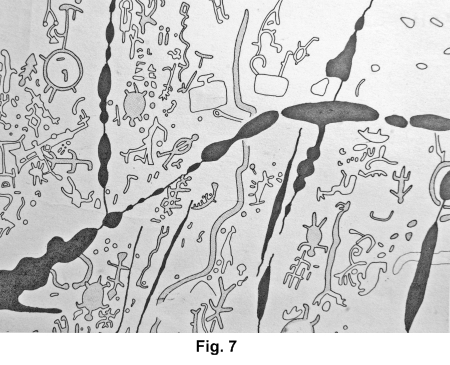

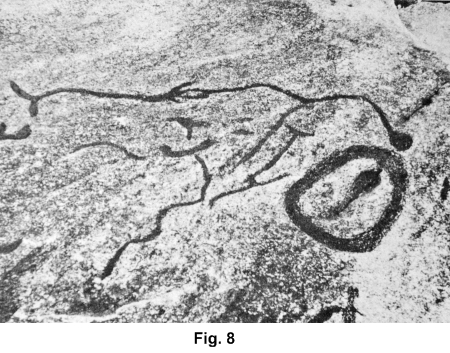

Whereas spirits may enter and leave cracks in rock, there is also a female connotation to them, based on the fact that the earth is considered feminine in that it gives birth and sustenance to all sorts of life forms. This was made visually apparent at the Peterborough petroglyph site in Ontario, Canada, where an open area of large limestone slabs has been elaborately pecked with dozens of petroglyphs. Numerous cavities carved out by water punctuate the limestone, and underneath water can be heard running. As the Vastokases have written in their important and fascinating book on this remarkable site, it was the combination of a number of numinous factors that made this such an important sacred site for the Algonkian Indians. Serpents have been carved leaving and entering the cracks (Fig. 7:the serpents are shown in the center of the image with the black void of the limestone in the middle), and two of these cavities have been transformed into vulvas (Fig. 8) (Vastokas & Vastokas, 50-52; 80).

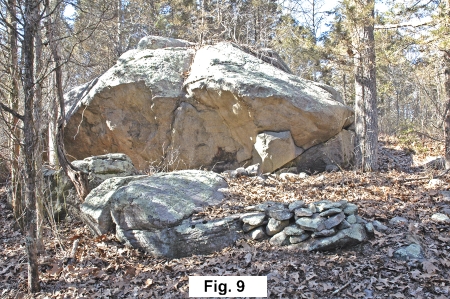

While the rock art sites in California have a shamanistic interpretation because of the petroglyphs found there, no petroglyphs have been found at the outcrop site in Hopkinton, RI, nor at any of the other sites I have examined. It is possible that the stone accents at the outcrop are the work of shamans, but it is also possible that such actions were done by Indian passers-by in a ritualistic and spiritual frame of mind over centuries and even millennia as they encountered the unusual outcrop and responded to its numinous character. As Jack Steinbring would say, the outcrop has phenomenal characteristics, given its location, shape, the deep fissures cutting across it, plus the attention it has been given by placing small rocks on and in it (Steinbring 1992, 102, 107). This is further emphasized as one continues around the outcrop to the south end, where large sections of stone have broken off in the distant past from frost action, leaving a weathered, angular surface (Fig. 9).

Most interesting, when observed in the oblique light of late spring afternoon a year ago, is a curious rock protrusion in the lower right portion of the outcrop, the remainder of the rock that broke off around it. Indians were aware of how light and shadow can create unusual shapes, turning an unspectacular rock formation seen in the flat light of an overcast day, into an animal or even a monster. To me, and in the right oblique light, the protrusion looks like a turtle head. Devereux (2000) would refer to this as a simulacrum, with the dome-like outcrop rising above like a carapace. The turtle was especially sacred to the Algonkians, symbolic of the earth and of fertility (Vastokas & Vastokas, 107), and in this particular location it makes sense, given the overall shape of the outcrop and the fissures that punctuate it. In flat, even light, the protrusion looks unremarkable (Fig. 10), but there is little doubt that attention was directed to this curious natural feature, for a small pile of stones is found at its base, and line of stones extends outward from it to touch a nearby boulder (visible in Fig. 9).From the lower end of this boulder a low wall begins and then dissolves into a curved line of single stones that ends just about in line with the protrusion, but does not touch the outcrop to complete a circle (see Fig. 10).Stone circles have been found adjacent to unusual boulders in New England. The circle could define a sacred space and draw attention to a strong spiritual source nearby, and this incomplete example could simply be a version of this.

The outcrop, the only one in the area, reveals its secrets only with careful study and an open mind. Most would probably walk past it and not know that they were seeing a visible reminder of an important cultural response, hundreds or even thousands of years old, to the rock landscape. Amazingly, southern New England and especially Rhode Island, is littered with examples of the Indian's response to the landscape. Larry Harrop and Peter Waksman (rockpiles.blogspot.com) have photographically recorded thousands of examples of native stonework over the past ten years which they have posted on their blogs and websites, and we can only hope that those who are entrusted with saving our past will eventually recognize the lithic riches that are within one's grasp.

*A similar version of this article previously appeared in the ESRARA Newsletter, Vol. 13,No. 3-4, Fall/Winter 2008-09, pp. 10-14.

Figures 7 and 8 are copied from Vastokas & Vastokas (1973). All other illustrations are by the author.

Bender, Herman, "Seeking Place: Living on and Learning from the Cultural Landscape," The Archaeology of Semiotics and the Social Order of Things, G. Nash and G. Children, eds., BAR International Series 1833, 2008, 45-70.

Devereux, Paul, The Sacred Place:The Ancient Origins of Holy and Mystical Sites, London 2000.

Dwight, Timothy, Travels in New-England and New-York, 3 volumes, New Haven 1821-22.

Muller, Norman, "Fahnestock Memorial State Park", Fahnestock Memorial State Park, 2007.

Muller, Norman, Accenting the Landscape: Interpreting the Oley Hills Site, The Archaeology of Semiotics and the Social Order of Things, G. Nash and G. Children, eds., BAR International Series 1833, 2008, 129-140.

Steinbring, Jack, "Phenomenal Attributes: Site Selection Factors in Rock Art." American Indian Rock Art, 17 (1992) 102-113.

Vastokas, Joan M and Romas K., Sacred Art of the Algonkians, Peterborough 1973.

Whitley, David S., et.al., "Sally's Rockshelter and the Archaeology of the Vision Quest," Cambridge Archaeological Journal 9:2 (1999), 221-247.