In September 1938, a monstrous and devastating hurricane swept through New England, flattening houses and uprooting trees as far north as central New Hampshire. It was probably the equivalent of the severe category five hurricane.

Shortly after the hurricane moved through Montville, Connecticut -- a small town about eight miles north of New London -- two teenagers, Mary Crouch and Carl Pilecki, were walking along the steep and lonely north slope of Beaver Dam Hill, not far from their homes, when they came upon a scene that undoubtedly startled them. Many trees had been uprooted by the storm, but one in particular caught their eye. A large oak tree had fallen, and in the process tore open a stone lined hole, four feet long by two feet wide and three feet deep (Fig. 1). We are not sure just what Mary and Carl did once they peered into the hole -- which was partly filled with dirt from the uprooted tree -- but perhaps they looked around and discovered that this was only a portion of a long tunnel-like structure, whose opening was some ten feet down slope and to the north. From this first discovery to the mid-1980s, we hear nothing about the structure. Presumably the two teens kept knowledge of this feature pretty much to themselves for the next forty-six years.

On October 28, 1984, the Norwich Sunday Bulletin carried an article by Sheri Venema titled Chambers Shrouded in Secrets, which told the story of two underground stone chambers that Charles Chase, a local resident, had found deep in the woods of Oakdale, just east of Montville. This site would later be referred to as the "Montville Complex". Mary Crouch read the article and recalled the strange passageway she and Carl had discovered as teenagers long ago. She telephoned Chase early in November and told him about the collapsed tunnel she had seen in 1938, thinking that he might be interested in seeing it, which of course he was. Mary was unclear as to precisely where she had seen it, but with the help of her old friend Carl, she was able to guide Chase to it.

Chase quickly realized the importance and uniqueness of the discovery. He contacted David Barron, president of the Gungywamp Society of Noank, Connecticut, who was one of the first to visit it that month. Barron, in turn, notified Jim Whittall, president of the Early Sites Research Society in Massachusetts, and together with Malcolm Pearson, a photographer, they visited the tunnel on December 2nd of that year.

Whittall had traveled extensively in Europe and was familiar with Bronze and Iron Age underground chambers, as was Barron. He concurred with Barron that the tunnel-like structure was similar to the fougos[1] or souterrains[2] both of them had seen in Ireland, Great Britain and Normandy. It was the similarity of the Montville tunnel to the European souterrains that gave the Montville example its appellation.

Whittall described this first visit in the December 1984 issue of the Early Sites Research Society Bulletin:

"To enter the passage, one must crawl through an opening 22" by 22" for a distance of 8 feet to a point where one can continue on hands and knees for another 20 feet. In a crouched position, the final distance can be covered to a little corbelled chamber at the end; a total distance of 37.5 feet from the entrance. The walls of the passageway are straight-sided, dressed drywall stonework, never exceeding 2 feet in width. The end wall of the chamber is cut into a ledge which has been roughly quarried to shape and level its contour. The souterrain is an architectural feat of determination on the part of the builders" (Whittall 1984: 7).

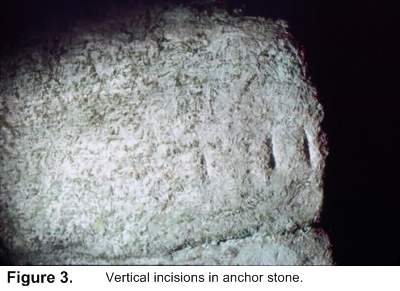

Pearson took photos of this visit, some of which were used to accompany Whittall's article (Fig. 2). At the same time, Barron had written a short article on the find for a 1984 issue of Stonewatch, the publication of the Gungywamp Society. All of this occurred at a time when the ideas of Barry Fell, a Harvard marine biologist turned antiquarian and epigrapher, were strongly held by a band of enthusiasts. Fell had written the popular book America B.C.in 1976, in which he concluded that Irish Celtic monks had visited North America in the early centuries of the Christian era and had constructed stone chambers. The souterrain fit nicely into the picture he drew of Celtic influences in the New World, and to cement this connection, Barron found three vertical incisions on the large anchor stone to the right of the entrance, which Fell concluded were Celtic ogam. These are perpendicular to the natural grain of the stone, and have been interpreted by two geologists as being man-made (Fig. 3). Fell concluded the lines signified the consonants L and B, and he combined these into the words "Lord Bel".

Much of what he wrote about ogam has been questioned, particularly his article that interpreted groove marks on a West Virginia cave wall as a Christian message (Fell 1983). This led to a sharply analyzed response by Oppenheimer & Wirtz (1989), and by Professor Brendan O'Herir, late professor of English at Berkeley and a Celtic scholar, who dissected Fell's interpretation of incisions on a cave in West Virginia (1983), in a lengthy unpublished manuscript of 1990 titled "Barry Fell's West Virginia Fraud.""

Is the Montville souterrain really a souterrain? This structure has been largely ignored by academic archaeologists, perhaps because it was discovered by a group of neo-antiquarians who seemed to have an agenda of lumping together the area's stone chambers and this unusual tunnel into a Celtic grab bag. Such an association and the people who promoted it were anathema to the archaeologists and were better left alone. Let us have a closer look.

The souterrain is found about 300 feet from a country road on the north side of a steep, rocky slope covered with tangled laurel and other underbrush This slope is often in shadow, because the ridge above blocks much of the sunlight. The combination of the rocky terrain, dense brush, and subdued light makes the area feel uninviting and slightly creepy.

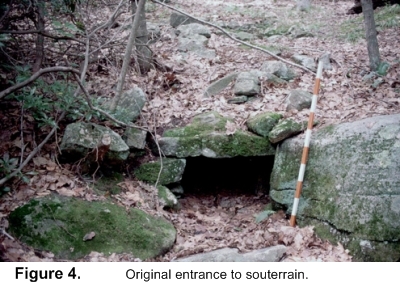

With no distinct landmarks in the vicinity, the

"souterrain" is difficult to find, and one is often

reduced to going back and forth across the hillside, climbing over

boulders and through tangles of laurel and vines, trying to find the

entrance, until with a good deal of luck one finally reaches a rotting

downed oak, over which the entrance comes into view (Fig. 4). David Barron once

described a large flat stone in front of the entrance that he felt

might have blocked it. There

is a notched stone just in front of the entrance that seems to fit the

bill, but I am unsure if this is the one he referred to. It is a little more than

three feet away and seems to be the right size, measuring 17"

high by 33" wide. One

side of this stone is rough, and it probably faced out. With the stone covering the entrance, the chamber

would have been nearly invisible, and this may be one reason why the

souterrain hasn't suffered more damage over time.

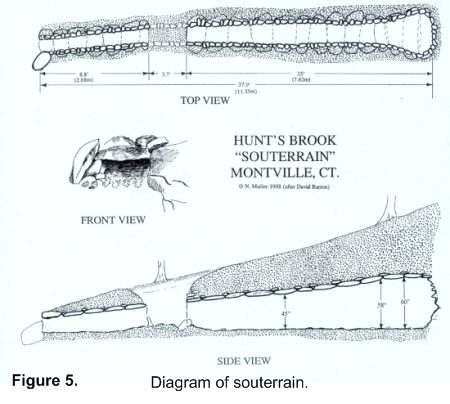

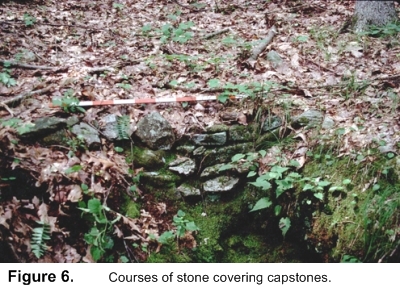

The souterrain was constructed by first digging a narrow channel nearly thirty-eight feet long and more than five feet deep into the ground to a rocky ledge, lining the sides with parallel courses of flat surfaced gneiss, a local stone, and then topping the walls with large, flat slabs of gneiss (Fig. 5). Smaller courses of gneiss were placed on top of the cap stones before the dirt was piled on. These are visible where the tree was uprooted (Fig. 6). A similar type construction, called a "comb roof" was found at a cist grave site near Sharpsburg, Maryland, in 1884 (Stewart 1981: 7). The dirt that was probably excavated from a ditch can be seen as low, indistinct mounds to either side of the souterrain.

The facade consists of

Rather than entering the souterrain through the real entrance, it is much easier to lower oneself into the collapsed portion, as Whittall and others have done, and then creep along the remaining twenty-five feet to the end. The actual tunnel is 37.9' long from the entrance to the back wall. It is a tight fit, with the width a narrow 24-26" and the height gradually increasing from 42" near the collapsed portion to 60" at the end (Fig. 7). This is not a place for a claustrophobic, or one fearful of large, albino spiders that inhabit the dark interior of the chamber. At the very end the tunnel widens into a beehive-like chamber built against a ledge that is just large enough to sit down in comfortably. It is not a very inviting place, and one doesn't care to linger there too long.

Whittall and Barron both concluded that the Montville 'souterrain" resembles those found in Ireland, which date from the Iron Age: ca A.D. 500-1000. Not having visited them or those in southern Britain, I am in a poor position to comment. Based on what I have read, however, the Montville example does bear a slight resemblance to those in the British Isles, except that the latter are generally much wider and taller, and also have side passages with a small entrance called a creep, such as we find in the fogou of Boleigh, in Cornwall. These examples date from about 100 B.C. to the first centuries of the Christian era, and various theories have been proposed as to their function, such as for storage or refuge, since they are generally close to human settlements. One other possibility, suggested by Ian Cooke in his book Mother and Sun, is that they had a religious or ceremonial function. I like this idea best of all with respect to the Montville structure. The outline of the souterrain as seen from above has the appearance of a serpent, with the chamber at the end representing the head (see Fig. 5).

The size and structure of the Montville souterrain make it highly unlikely that it was used for any kind of storage: the constricted size of the entrance and tunnel and the length of the passageway to the small chamber at the end contradict this interpretation. It is certainly unlike any of the stone chambers Neudorfer said were used for storage (1980). In fact, the narrow entrance implies that it was deliberately constructed to make it difficult to enter. Perhaps it was intended to be a frightening experience for those entering the darkened interior without the aid of a light source. Furthermore, unlike the fogous or souterrains of Britain, it is not near any former settlement. Instead, it located on a lonely, dark hill, far from the road, and surrounded only by dozens of stone cairns of various shapes perched on boulders, which seem to begin at about the same level on the hill and extend up to the summit (Mavor & Dix 1989: 259). It is on the east end of the ridge, that one finds the large, fractured, perched boulder of gneiss, in which the bottom section has seemingly been pushed out of place, perhaps by frost action (Mavor & Dix 1989: 111c) The same kind of violent rupture occurred in a split boulder in the Morgan R. Cheney Audubon Sanctuary nearby. Severely fractured and offset boulders such as these seem commonplace in Montville, and many of them appear to have been ritualized by placing stones on them and between the broken segments. Could these, I wonder, have been dislodged around the same time, perhaps during a short period of extremely severe weather, or even from the effects of a violent earthquake?

Viewed against the backdrop of Montville history, certain aspects of the souterrain begin to be clarified. Montville is a small town situated on the west side of the Thames River, halfway between New London and Norwich, and was formerly called the North Parish of New London. It was first settled in 1653 by Richard Houghton and James Rogers, who were granted land by Uncas, the Mohegan chieftain. In 1703, North Parish was added to New London by a grant of the General Court, but Montville was not incorporated as a town until the mid-1700s.

Beaver Dam Hill, on which the "souterrain" is found, was part of an area designated as "common land" on a 1730 map prepared by Joshua Hempsted, a county surveyor, as was the large and ill defined area to the north across Hunt's Brook. A copy of this map is in the Raymond, Connecticut, public library. This land was not deeded to anyone, but was for the use of the townsfolk, perhaps for wood harvesting. Small farms at this time were clustered around Unger or Moxley Street, about three-quarters of a mile southeast of Beaver Dam Hill, where Fire Street now begins, and near the junction of Fire Street and East Lake Road to the west. The area in between was not developed until Fire Street was laid out in 1772. Thereafter, a couple of farmhouses were constructed west of the junction with Unger Street, but none in the immediate vicinity of the souterrain. One of the farmhouses on the west end of Fire Street belonged to a C. Beckwith, who had built a sawmill along Hunt's or Alewife Brook, just northwest of the souterrain, across the brook. The mill may have become operational just after the road was surveyed and laid out, and it remained viable until at least 1854, after which it was abandoned.

There is no physical evidence that the land around the souterrain was ever inhabited. No old cellar holes dot the hillside, and there are no stone walls defining property lines except some on the other side of Beaver Dam Hill. The terrain is steep and rocky and hardly suitable for farming.

Sal Trento, in his book Field Guide to Mysterious Places of Eastern North America, conveys the story that in the early 1600s the land on which the souterrain is found was originally given to a John Brown, who was a crew mate of John Winthrop, an early governor of Massachusetts. Trento states: "When Brown died he had no heirs, and he did not leave the land to any of his friends. For unknown reasons, no one during the last 160 years squatted or claimed the land. It has mysteriously avoided ownership, almost as if it were cursed soil." However fascinating the story, I have found no truth to it.

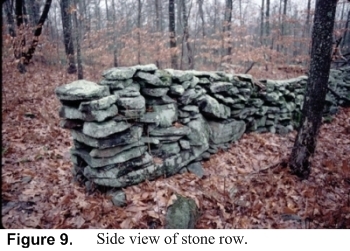

A clue to the original function of the souterrain may lie with a curious and very well made stone row, 147 feet long, situated several hundred feet west [3]. During the colonial period, walls were generally constructed of stones dislodged in fields by plowing, and were carried by stone boat to the edges of the field, where they were piled into the rustic walls that define the New England landscape. Many of them form networks with other walls. However, the one on Beaver Dam Hill is different, in that it is an isolated segment with no indication that it was ever connected to a wooden rail fence. A trace of low stones beyond where the present wall begins and ends would provide a clue that a rail fence continued at either end, but nothing of the sort is to be found. Instead, the wall or row in question is finished at both ends, implying a function quite distinct from the usual colonial usage. Some of the boulders comprising it are huge: one is six feet long, a foot thick and two feet wide, and weighs close to a ton. I believe the row bears a direct relationship to the souterrain.

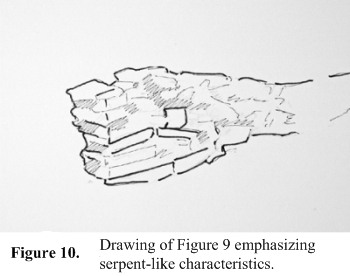

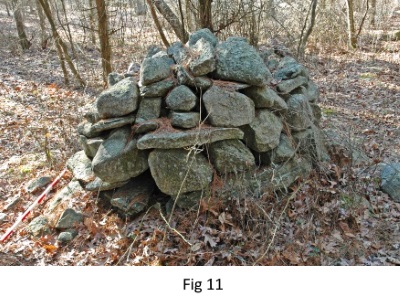

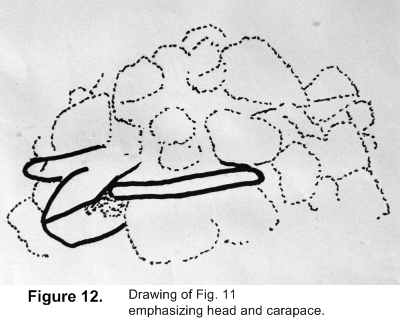

As viewed head on at the top, the row has a curious, repetitive post-and-lintel construction (Fig. 8), consisting of one or two smaller rocks supporting a larger, flat slab. However, when viewed from the side, (Fig. 9), the pattern of stones seems to merge into the shape and detail of a serpent's head, with an unusual square stone representing the eye, and the arrangement of long rectangular stones below, the mouth (Fig. 10). Some may say I am reading too much into the stone arrangement, but Indian stone constructions representing snakes or turtles are often very subtle, with only a few accents providing a clue as to what they represented. For example, a stone mound in Hopkinton, Rhode Island might look like just another pile (Fig. 11), but Doug Harris, Historic Preservation Officer of the Narragansett Tribe, pointed out that one stone represents a head, and two other flat stones are suggestive of the carapace (Fig. 12).

As we follow the stone wall down slope to the north, off to the left (west), is a small stone circle, within which are some carefully laid flat slabs (Fig. 13). It is hard to know what this feature represents, or even whether it is very old. The carefully laid stone base is curious, and while some might conclude that it was a fireplace, I have found no evidence of charcoal or carbon residue on the stones.

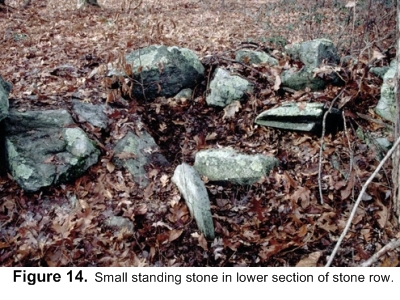

A bit farther north from this point is a disturbed portion of the row that might be interpreted as a spot where a tree fell. It is about 25 feet from the end of the row, which concludes in a step and is finished the same way as the other end. What I find interesting about this spot, which measures about eight feet across and three feet wide, is that in the center is an upright curved stone, firmly embedded in the ground and pointing almost due east (Fig. 14).

The small standing stone is shown at the bottom center of the image on edge. By taking a compass bearing along the axis of the stone, and using a long tape measure, I was able to determine that the stone pointed to within ten feet of the opening of the souterrain. Was this sheer coincidence? I'm not so sure. There also seemed to be a line of cairns leading in the direction of the souterrain. Assuming the row does represent a serpent, the location of the small upright stone and disturbed portion of the row is located near the cloaca of a live snake from which eggs are laid. Snakes were considered powerful and generally dangerous creatures associated with the underworld, and were able to transform themselves by shedding their old skin. We might hypothesize a connection between the stone row and the "souterrain" involving ritualistic birth and rebirth in a vision quest ritual. If this were the case, an initiate could have crawled down the length of the souterrain and remained there for a day or more, an undoubtedly frightening experience, which might have symbolized being swallowed and eventually reborn.

It should be pointed out that stone snake effigies are not uncommon in the Northeast. Two have been found on Overlook Mountain in Woodstock, NY. One was mentioned by Glenn Kreisberg in his article The California Quarry and Nearby Stone Cairns of Woodstock, NY (Kreisberg 2007). A web article on a possible water serpent in Vermont listed other examples of stone serpents (Muller 2007)

Any proposed explanation of the souterrain comes up against the dilemma that there is nothing else quite like it in New England. David Barron once showed me a photograph of a similar tunnel like structure with capstones that was uncovered in New London years ago. There is also the long complex of tunnels with capstones in Goshen, Massachusetts, that were examined by Whittall and later Trento (1997: 149-155). None of these is exactly like the Montville example, although their construction is similar. If the possibilities I have advanced above have any validity, they should be substantiated by similar examples, but the souterrain is the only feature of its type that has been discovered in New England.

In December 1984, Whittall wrote a letter, together with maps and drawings of the souterrain, to Terry Ross, a well-known dowser. Whittall asked Ross to conduct pendulum dowsing on the materials in order to help answer the questions surrounding the structure. Whittall asked Ross to try to determine when the structure was built, to which Ross replied about 310 B.C. Whittall also inquired about what it was used for, and Ross responded that it might have been used as a ceremonial or ritual "temple". Finally, Whittall asked where there might be found similar structures. Ross pinpointed two locations north of the souterrain, in the area near the "Montville Complex", where there are two unusual stone chambers (Barron 1984b; Venema 1984). Neither of these possible sites has been checked out.

While a number of people have crawled the length of the "souterrain", and have speculated about its use, all comments, including my own, have been based largely on simple observation, not material analysis. It is this last methodology that should be addressed. We could start with the interior, which has not been overly disturbed. Until the souterrain was rediscovered in 1984, it is doubtful if anyone had crawled the length of the tunnel in modern times, since dirt had obstructed the portion where the tree had been uprooted. There is no evidence the souterrain was known prior to 1938. Thus, whatever might be discovered on the floor of the tunnel and in the chamber at the very end could be very significant. This might involve analyzing the dirt and anything found in it, such as pollen, plus the soil covering the capstones. To do this, one would have to get in touch with the present owner, whoever that might be. When I inquired about ownership ten or so years ago, I was told that the owner's surname was Dart, and that no taxes had been paid on the property for more than 100 years! This might present an opportunity to purchase the souterrain and the property around it outright, and then conduct a sensitive excavation to determine, once and for all, when the feature was constructed, which, in turn, might help in determining its original purpose. As one of the most intriguing stone features in all the Northeast, the souterrain is certainly worthy of further study.

This article was previously published in the NEARA Journal, vol. 41, no. 2, Winter 2007.

Barron, David 1984. Hunt's Brook Site Souterrain -- Fabulous Discovery! Stonewatch, Newsletter of the Gungywamp Society, 4.

-- -- -- , 1984b. Atrium Chamber Site (C6-25), Montville, Connecticut, Early Sites Research Society Bulletin, 11 (1), 3-6.

Cooke, Ian M. 1993. Mother and Sun: The Cornish Fogou, Cornwall.

Fell, Barry 1983. Christian Messages in Old Irish Script Deciphered from Rock Carvings in W. VA, Wonderful West Virginia 47 (1), (1983), 12-19. Also posted online at http://cwva.org/wwvrunes/wwvrunes_3.html.

Kreisberg, Glenn 2007. The California Quarry and Nearby Stone Cairns of Woodstock, NY, NEARA Journal. California Quarry, Glenn Kreisberg, NEARA Journal 41.1 2007.pdf.

Mavor, James & Byron Dix, 1989. Manitou, Rochester, VT.

Muller, Norman 2007. A Possible Water Serpent Effigy at Site R7-2, Rochester, Vermont, Site R7-2.

Neudorfer, Giovanna 1980. Vermont's Stone Chambers: An Inquiry Into Their Past. Vermont Historical Society, Barre.

O'Herir, Brendan 1990. Barry Fell's West Virginia Fraud. An unpublished manuscript written in response to Barry Fell's article in Wonderful West Virginia.

Oppenheimer, Monroe & Willard Wirtz, 1989. A Linguistic Analysis of Some West Virginia Petroglyphs, The West Virginia Archaeologist 41 (1), 1-6. Also posted online at http://cwva.org/ogam_rebutal/wirtz.html

Stewart, R. Michael 1981. Prehistoric Burial Mounds in the Great Valley of Maryland, Maryland Archaeology 17, 1-16.

Trento, Salvatore 1997. Field Guide to Mysterious Places of Eastern North America, New York, 181-185.

Venema, Sheri 1984. Chambers shrouded in secrets, Norwich Sunday Bulletin, October 28, 20.

Whittall, James II 1984. Hunt's Brook Site Souterrain Montville, Connecticut, Early Sites Research Society Bulletin, 11/1, 7-12.

[1] Fogou -- Cornish word for cave or underground chamber.

[2] Souterrain -- from French sous terrain (under ground) is a name given by archaeologists to a type of underground structure associated mainly with the Atlantic Iron Age. These structures appear to have been brought northwards from Gaul during the late Iron age. Regional names includes earth houses, fogous and Pictish houses. They are often referred to locally in Ireland simply as "caves". https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Souterrain.

[3] See Mavor & Dix, p. 259, Fig. 10-7; the stone row is the feature to the left of point A (souterrain) on the map.