NEARA’s interest in OSL dating continues. This time we visited a lab where the OSL dating is actually performed. To learn more about OSL dating please read: Wikipedia: Luminescence Dating

The Luminescence Dating Research Laboratory at Stony Brook University was established by Assistant Professor Marine Frouin, opening just this summer. It is the only such lab in the northeastern US. More information about the lab is at: marinefrouin.com

Harvey Buford arranged for us to tour the lab in August. He, Dyane Plunkett, Vance Tiede, Gary and Cynthia Aliçandro, Alison Guinness and I took an early morning car ferry from New London CT to Orient Point NY on Long Island. The day was pleasant and it was fun going on a boat ride.

The lab is part of Stony Brook’s Department of Geosciences and the Turkana Basin Institute. There are five rooms, three of which are “dark” for storing and preparing samples, extracting quartz and feldspar grains, and measuring their luminescence. No cameras or cellphones are permitted in the dark rooms of the lab, so we didn't take as many photos as we would have liked. The following photos in the dark rooms were provided by Dr. Frouin.

Before preparing and measuring the samples in the darkroom, some analyses are made in the “white” lab on materials associated with the samples.

There they examine the size and shape of the grains. Aeolian (wind-borne) deposits are more likely to be rounded; fluvial (river) deposits are more likely angular. A more uniform size mixture usually implies that the deposition of the grains resulted from a one-time event, which means there is less of a risk of post-depositional mixing or contamination.

The metal sieves range from 45 µm to several mm. To avoid accidental physical contamination, these sieves are not used on the actual material from which the grains are taken to be measured.

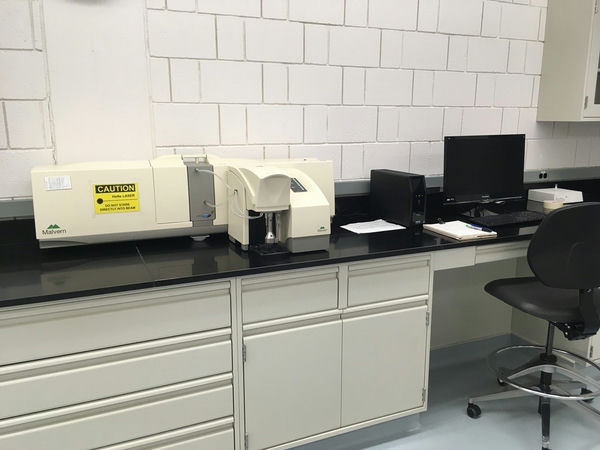

The grain size measurement is done with sieving and a laser grain size analyzer. This information is useful for helping to interpret the results.

There is also a separate box used to artificially "bleach" samples with a light that is seven times as bright as the sun.

One of the interesting features of the lab is a revolving door to prevent light from entering the dark rooms when people enter or exit.

It’s important that samples are not exposed to any light of particular wavelengths before they are measured. So how do lab personnel prepare the samples and extract the right grains of quartz or feldspar for measurement? Fortunately, it turns out that a fairly pure amber light (~595nm) permits visibility for handling the samples without compromising the results. As part of the construction of the lab, Dr. Frouin set up custom interior lights composed of LEDs with orange filters.

Dr. Frouin’s practical creativity was apparent not just for the lighting but also at several stages of the OSL dating process. To improve the sieving process, she designed homemade sieves for the initial separation of the sample materials. To avoid possible contamination, it’s important to use disposable filters –- one cannot see any left-over grains that are stuck in a fine screen when they are that small. But commercially available sieves are too small, so she had to design nested funnels holding the nylon mesh filters. Alas, the mesh material is still fairly expensive: $500-$800/20 yards. She frequently shares information about techniques and procedures with other labs so that everyone can learn how to do things better.

They typically desire for measurement a grain size that is between 90 to 255 µm, but measurements could be made on grains as small as 4 µm.

There is an ultrasonic bath to help separate aggregates of sediment before sieving. They remove carbonates and organics with hydrochloric acid and peroxide.

In order to separate the quartz grains from the feldspar grains and from other materials, they use a very dense liquid: sodium metatungstate. It has a density of 2.82g/cm3, almost three times the density of pure water, and it feels remarkably heavy for a water mixture! They adjust the density to match that of quartz so that the other materials either float or sink. A centrifuge speeds up the separation. To ensure that the quartz is pure, they dissolve any remaining feldspar with hydrofluoric acid.

There are separate ventilated fume hood chambers for dealing with the noxious fumes produced during sample preparation.

The luminescence-reading machine is made by Risø. It is a simpler model and cost about $90K.

They have ordered a new attachment to this reader to analyze the composition of the samples directly in the reader, as well as an additional Risø reader with a laser that will support testing single-grain aliquots; the laser itself is approximately an additional $65K. A description of the machine and its options is at: Risø TL/OSL Reader

In the basement there is a huge lead-lined radiation measurement device (Broad Energy Germanium Detector) that cost approximately $120K. Materials are placed deep inside the cylindrical structure and are typically measured for gamma radiation for 4 days in order to get a good reading. Unlike a typical Geiger counter, the device measures a broad spectrum of energies, which helps determine the nature of the sources of the radiation. The measurements are needed in order to help determine how much radiation the samples were exposed to while they were in the ground.

The trip was very pleasant and informative, helping us understand more about the OSL dating process and appreciate the lab work involved in preparing for measurements and interpreting the data.

A special thanks goes to Dr. Marine Frouin for giving us a tour of the labs, answering so many of our questions, and providing some photos of the dark rooms.

The NEARA Research Committee promotes research by soliciting and recommending and funding projects, setting guidelines and standards, and maintaining site information. For more information, contact us at research@neara.org.