Contact the coordinator at MA-coord@neara.org

Many of the sites described in Mavor and Dix’s seminal book on New England ritual landscapes can be found in Massachusetts. These include the Upton Chamber, Boxboro esker, and Nashoba praying village. Massachusetts is also home to one of the most debated petroglyph boulders in New England, Dighton Rock, as well as the enigmatic engraving of a sword hilt ascribed to “The Westford Knight”. In spite of centuries of urban development, old stone chambers, configurations of stone cairns, and winding stone walls are still being discovered off the beaten track, leaving us with many curious artifacts to ponder.

The Massachusetts landscape was carved out by glaciers during the last ice age. When the glaciers retreated around ten thousand years ago, they left behind heaps of stone debris, long ridges, huge erratics, and broad drumlins.

We know that Native Americans were building with stone here as early as 5000 years ago; a salvage excavation of a rock shelter in Marlborough revealed a stone wall 15 feet long and 2 feet high, framing the base of a winter habitation site beneath the overhanging ridge. Pre-Columbian Indians used controlled burns to manage woodland and often kept some hills cleared of trees altogether. Thus, when Europeans arrived in the 1600’s, they found a familiar landscape with parkland, stone walls, and agricultural fields.

Disease, war and persecution decimated New England’s Indian population, resulting in the loss of much local knowledge of Native American stonework. Although old accounts describe the Indians’ use of stone chambers as sweat lodges and mention their construction of stone and stick piles to honor a spirit or ancestor, by the late twentieth century it was commonly assumed that New England’s aborigines “did not build in stone.” Stone chambers were simply designated as root cellars or ice houses and stone piles dismissed as farm clearing piles. It took two Massachusetts residents, James Mavor and Byron Dix, to rethink such structures as the remnants of a vast ritual landscape. Their 1989 book, Manitou, makes a compelling case that New England’s Native Americans employed stone for a variety of purposes, including even astronomy. Support for this interpretation has been growing, exemplified by a 2009 finding by the federal government that a stone site near the Turners Falls Airport once served as a sacred ceremonial hill, eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

Some writers, seeing a similarity between the stone chambers in New England and Britain, have speculated that pre-Columbian Celtic contact must be responsible. Others are convinced that Vikings made it to Massachusetts shores; in fact, there is a stone tower in Waltham commemorating Lief Erikson’s discovery of the Charles River in 1000 A.D.! Engravings of a sword and boat found in Westford have been taken as evidence of a 14th century voyage by Scottish earl Henry Sinclair, while enigmatic carvings on a boulder in the Taunton River have been ascribed to early Portuguese navigators and even Phoenicians.

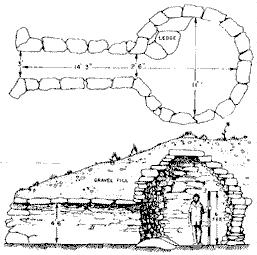

Few structures in Massachusetts have generated as much controversy as the Upton Chamber. Nestled in a valley near Upton’s Pratt Pond, the chamber’s narrow 15-foot long tunnel leads to a domed room 10 feet wide and 10 feet high. The beehive architecture so resembles that of Irish monastic cells that William Goodwin featured it in his 1946 book as evidence for a pre-Columbian settlement of Culdee monks. Mavor and Dix suspected a Native American origin and noted that horizon features on a facing hill set up visual alignments marking the summer solstice sunset and the heliacal setting of the Pleiades. Those favoring a colonial interpretation point to historical records showing that a tannery once existed not far from the site. Archaeological studies have thus far yielded few clues. Fortunately, thanks to the efforts of the Upton Historical Commission, the area surrounding the chamber has been preserved as a park, and perhaps someday its true origins and purpose may yet be determined.

Like the Upton Chamber, the engraved boulder that once greeted travelers coming up the Taunton River, has generated many diverse interpretations. Chisled into the stone, one can recognize animal and humanoid forms among more abstract designs resembling X’s and diamonds. Some see Roman numerals, dates, and even a Portuguese coat of arms among the engravings, and it is quite likely that inscriptions were added at multiple times over the centuries. But based upon similarities to other Native American petroglyphs, most, if not all of the figures probably have an indigenous origin.

A 3D model of the surface, produced by a laser scan in 2015, is now interactively viewable at Dighton Rock 3D Scans.

Scattered about the Foxboro State Forest are a number of U-shaped stone configurations. Elsewhere in the Americas, similar enclosures have been identified as Indian prayer seats, sites where an individual or group might go to seek a vision or observe the heavens. Those in Foxboro range in size from a small U that can fit one person to a massive structure that could accommodate a dozen.

Chuck Drayton compiled detailed site information that we are now hosting at: Foxboro State Forest stone sites.

Stephen Carney has a number of videos on YouTube about these same sites: Stones and Stories.

Located on conservation land in Sharon, King Philip’s Cave is a natural cluster of large boulders with two unusual properties. From the center of the cave, one can observe the summer solstice sun set on the horizon through a narrow stone aperture created by what appears to be a worked slab. From the same spot, one can observe a dagger of light disappear into another crevice on the winter solstice. Historically, the area was known as an important Indian site. “King Philip” was the English name for Metacomet, the Indian chief who led the ill-fated uprising against colonial invaders in 1675. One can only wonder whether the astronomical properties of the cave were recognized and utilized by the Indians, for whom the solstices were significant events and celebrated by ritual.

The Middleborough area has a number of contact period petroglyphs, many comprising life sized hand prints pecked into boulders or bedrock. Perhaps this was a way of marking ownership of the property. A description by Nehemiah Bennett dated 1793 mentions "a rock on a high hill a little to the eastward of the old stone fishing weir, where there is the print of a person's hand in said rock". [Massachusetts Historical Collections Vol. 3d 1810]. According to local legend, during the King Philip’s War, an Indian who was taunting the English at a nearby garrison was shot and killed at the boulder. The handprint was supposedly left as the dying Indian’s hand struck the stone. The carving may have been “enhanced” in the 1930’s to make the outline deeper, so we don’t know if the curved wrist and lines on the palm were in the original engraving.

3D models of all of the hands that we have found so far are available for interactive viewing at Middleborough Petroglyph Hands.

A resident of Boxboro, Manitou co-author Byron Dix predicted that the winter solstice sun would rise above an animal shaped boulder when viewed from a stone platform within a wall on the far side of a field. His prediction was verified when the midwinter sun did indeed appear in a v-shaped notch in the effigy boulder. The site is now under the protection of the Sudbury Valley Trustees and neighbor and NEARA member George Krusen offers a morning sunrise tour there every December. Curiously, a stone cairn visible from the same viewing point serves as a horizon marker for the summer solstice sunrise.

Stone pile sites can be found all over Massachusetts. In some cases, the stones are carefully arranged on top of exposed boulders. In others, they appear loosely piled on the ground. Often, they are found in large clusters of similar appearance. While some may be the result of field clearance, many are found in areas so rocky that “field clearing” would have been futile. There are some early New England accounts of Indians building "donation piles", in which travelers add a stone or stick to a pile to honor an ancestor or local spirit. Elsewhere, stone piles are associated with vision quests. Wildcat Hill, located in Ashland not far from one of John Elliot’s praying villages, may have comprised a ritual landscape with upwards of a hundred devotional cairns, all on the west slope of the hill. If you visit a stone pile site, enjoy the ambience and take care not to disturb any of the rock formations, which contemporary Native Americans believe still carry prayers to Mother Earth.

Pecked in the bedrock close to the center of Westford is what appears to be the hilt of a sword. It is claimed that the outline of a knight with shield and sword was once visible here, although natural striations in the bedrock might have accounted for much of the image. Known as the “Westford Knight”, some relate the carving to an account of a sea voyage taken by Scottish earl Henry Sinclair in the 14th century. Adding to the mystery is a carving of a sailing ship, arrow and what appear to be numbers on a small stone, now housed in the Westford Library.

Known locally as the “Acton Potato Cave”, this recently restored stone chamber may have been utilized as a root cellar. It may also have had a previous life as an Indian ritual chamber. The underground cell is one stop along the “Trail Through Time”, a heritage trail connecting up both colonial and Native American sites which include an old mill, pencil factory, and a large cluster of Indian stone piles. The close proximity, overlap, and reuse of diverse cultural artifacts is typical of the Massachusetts landscape, and one of the reasons that the origins of many of the state’s unusual lithic features remain a mystery.

A visit to a dig site on Cole's Hill in Plymouth MA: Digging for Vestiges of Old Plymouth

A model of the actual engraving that inspired the NEARA logo:

Andrew Fiske Center for Archaeological Research (U Mass)

Boston University Archaeology Department

City of Boston Archaeology program

Dan Boudillion's field journal

Massachusetts Archaeological Society

Massachusetts Historical Commission

Western Massachusetts Society of Archaeology